Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future

The report

Looking back at the past 50 years, the world has changed in many ways – but not in the direction called for in June 1972 at the UN Conference on the Human Environment.

This year’s UN international meeting marking that event, ‘Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all – our responsibility, our opportunity’, held in Stockholm on 2–3 June 2022, takes place in an alarming context: we face intertwined crises of the state of our planet and extreme inequality among people and societies. The Covid-19 pandemic continues to slow or reverse progress. And geopolitical shifts highlight our interconnectedness and vulnerabilities more than ever.

Today, the track record to deliver on the ambitions of half a century ago remains poor. We need to leave behind a new legacy: Stockholm+50 can be a watershed moment for unlocking change that is substantial and systemic.

A new report that is a collaboration between the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) makes recommendations for that legacy, with actions relevant to the Stockholm+50 meeting.

The report Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future synthesizes up-to-date scientific evidence and analyses the intertwined human and environmental crisis facing the world today. It presents key actions that can be taken now to seed transformative change and that are needed to redefine the relationship between humans and nature, ensure lasting prosperity for all, and invest in a better future.

The report makes further recommendations for improving the conditions for change through improved policy coherence, strengthened accountability, and renewed multilateralism built on solidarity for our common challenges.

Written independently by SEI and CEEW researchers, with funding from the Swedish Ministry for the Environment, the report is based on background papers and insights from the scientific community and our partners, as well as keystone reports from relevant organizations and community actors. An advisory panel consisting of 27 experts in the field of sustainable development science and policy has guided the work.

In association with this report, a team of early career researchers at SEI and CEEW have prepared the report Charting a Youth Vision for a Just and Sustainable Future, presenting key actions for reaching a sustainable future from a youth perspective, as articulated by young people themselves.

The report

Looking back at the past 50 years, the world has changed in many ways – but not in the direction called for in June 1972 at the UN Conference on the Human Environment.

This year’s UN international meeting marking that event, ‘Stockholm+50: a healthy planet for the prosperity of all – our responsibility, our opportunity’, held in Stockholm on 2–3 June 2022, takes place in an alarming context: we face intertwined crises of the state of our planet and extreme inequality among people and societies. The Covid-19 pandemic continues to slow or reverse progress. And geopolitical shifts highlight our interconnectedness and vulnerabilities more than ever.

Today, the track record to deliver on the ambitions of half a century ago remains poor. We need to leave behind a new legacy: Stockholm+50 can be a watershed moment for unlocking change that is substantial and systemic.

A new report that is a collaboration between the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) makes recommendations for that legacy, with actions relevant to the Stockholm+50 meeting.

The report Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future synthesizes up-to-date scientific evidence and analyses the intertwined human and environmental crisis facing the world today. It presents key actions that can be taken now to seed transformative change and that are needed to redefine the relationship between humans and nature, ensure lasting prosperity for all, and invest in a better future.

The report makes further recommendations for improving the conditions for change through improved policy coherence, strengthened accountability, and renewed multilateralism built on solidarity for our common challenges.

Written independently by SEI and CEEW researchers, with funding from the Swedish Ministry for the Environment, the report is based on background papers and insights from the scientific community and our partners, as well as keystone reports from relevant organizations and community actors. An advisory panel consisting of 27 experts in the field of sustainable development science and policy has guided the work.

In association with this report, a team of early career researchers at SEI and CEEW have prepared the report Charting a Youth Vision for a Just and Sustainable Future, presenting key actions for reaching a sustainable future from a youth perspective, as articulated by young people themselves.

We have the knowledge we need to act for a sustainable future.

We must now move past the barriers that have held back action in the past, to transform our systems.

If we unlock transformation and accelerate the pace of change now, we won’t need Stockholm+100.

Watershed moments

The world we live in now is very different from 1972, and from the future we want.

Fifty years after Stockholm 1972, humans are causing unprecedented change to the global environment and are risking tipping points with major and irreversible changes in our lifetimes. Climate change has already caused widespread adverse impacts to nature and people, and limiting global warming to 1.5°C is beyond reach without immediate, rapid and large-scale reduction of emissions. Biodiversity and ecosystems are deteriorating worldwide, and goals for conserving and sustainably using nature cannot be met by current trajectories.

Unsustainable production and consumption patterns put a healthy planet and sustainable development at risk. The use of natural resources has more than tripled from 1970, and continues to grow.

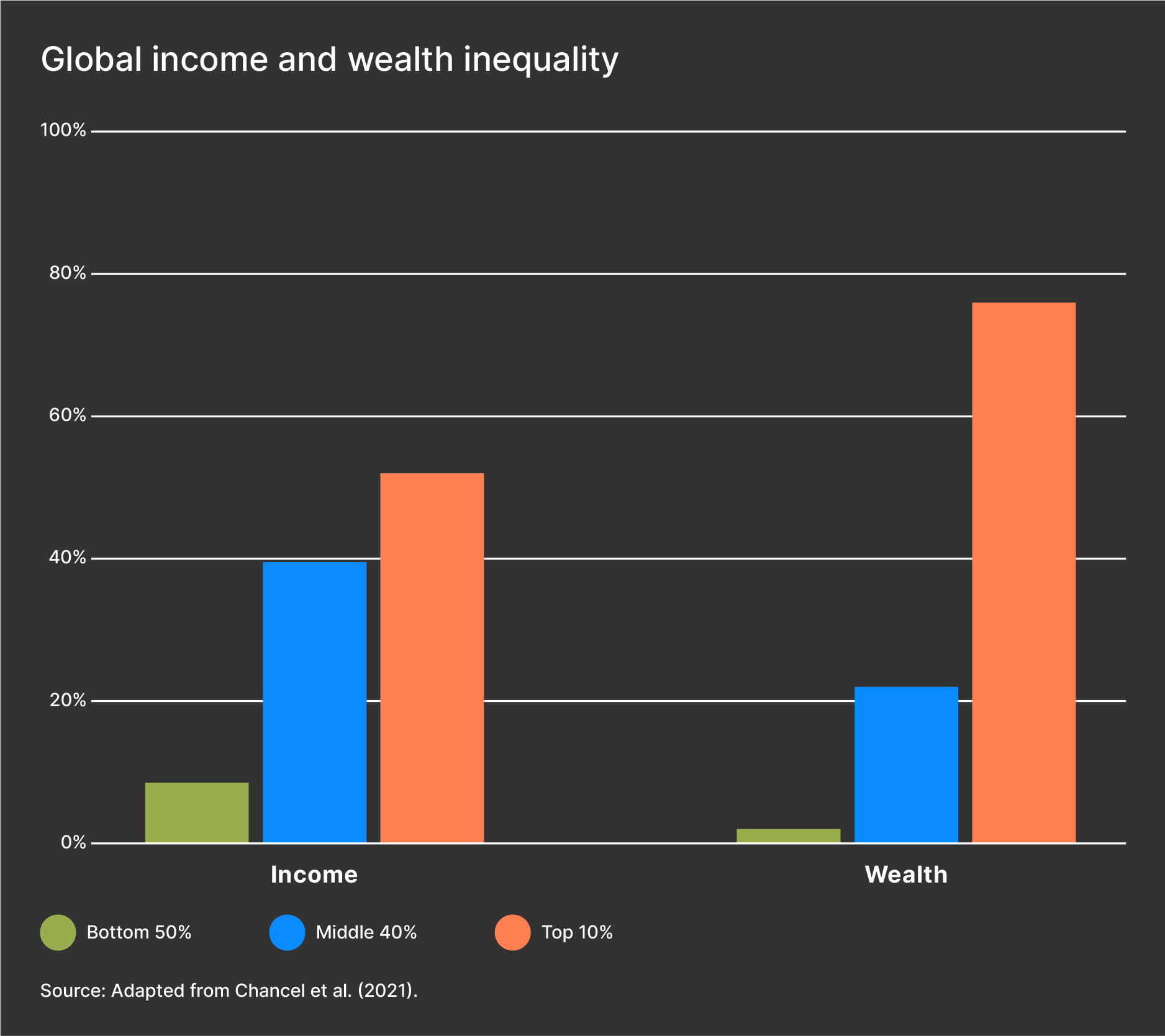

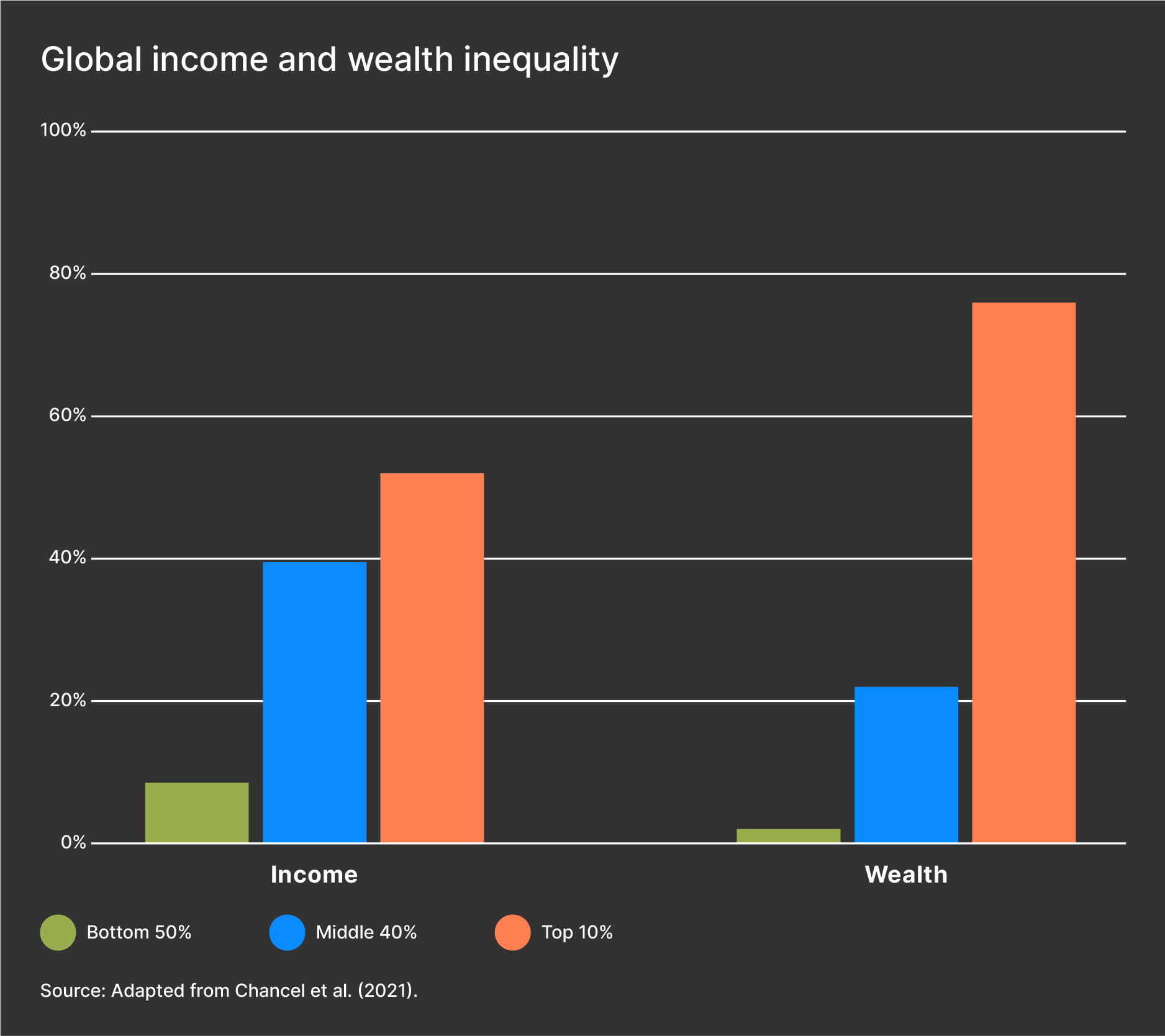

The use of these resources and their benefits are unevenly distributed across countries and regions. Inequality is immense, between nations and within nations. The social and economic costs of inaction are predominantly borne by the poorest and most vulnerable in society, including Indigenous and local communities, particularly in developing countries.

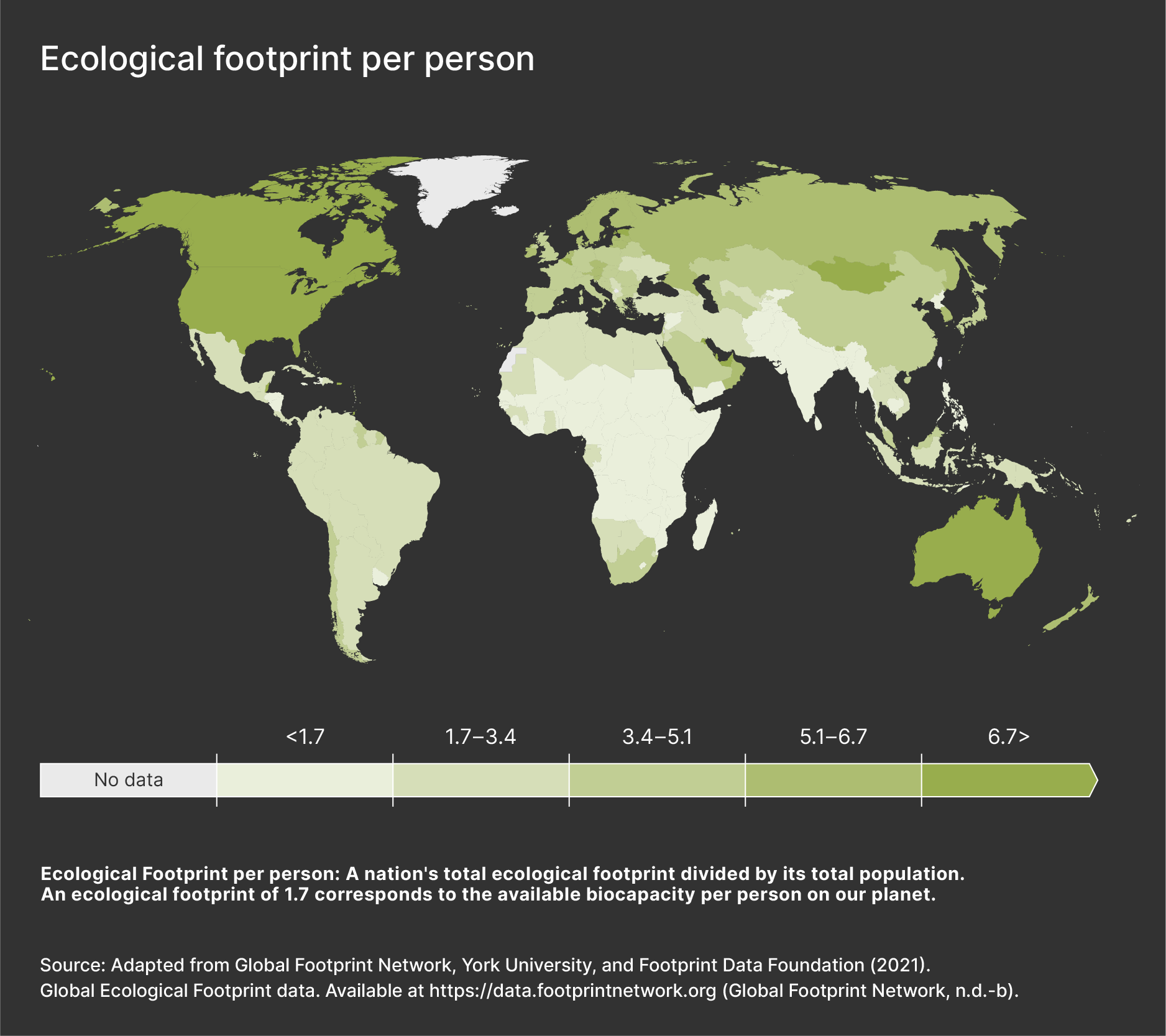

The growing inequalities extend to future generations and the quality of their lives, with accelerating environmental change and increased risk of breaching tipping points. High-income countries must drastically reduce their footprints, especially in light of their cumulative footprints over time, to avoid closing development pathways for low-income countries and future generations. This requires transformative action and addressing our economic systems as the core driver of many of these problems.

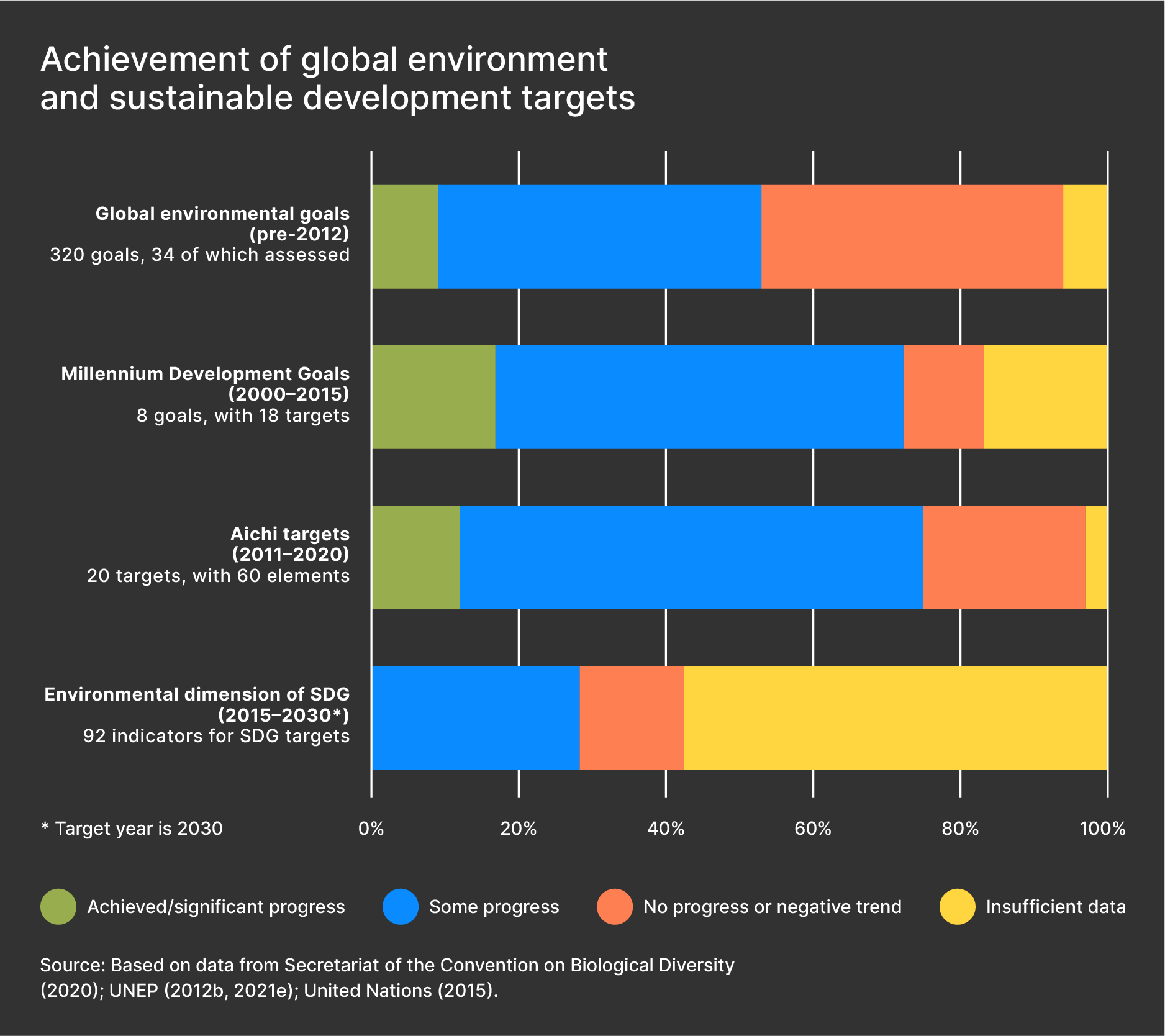

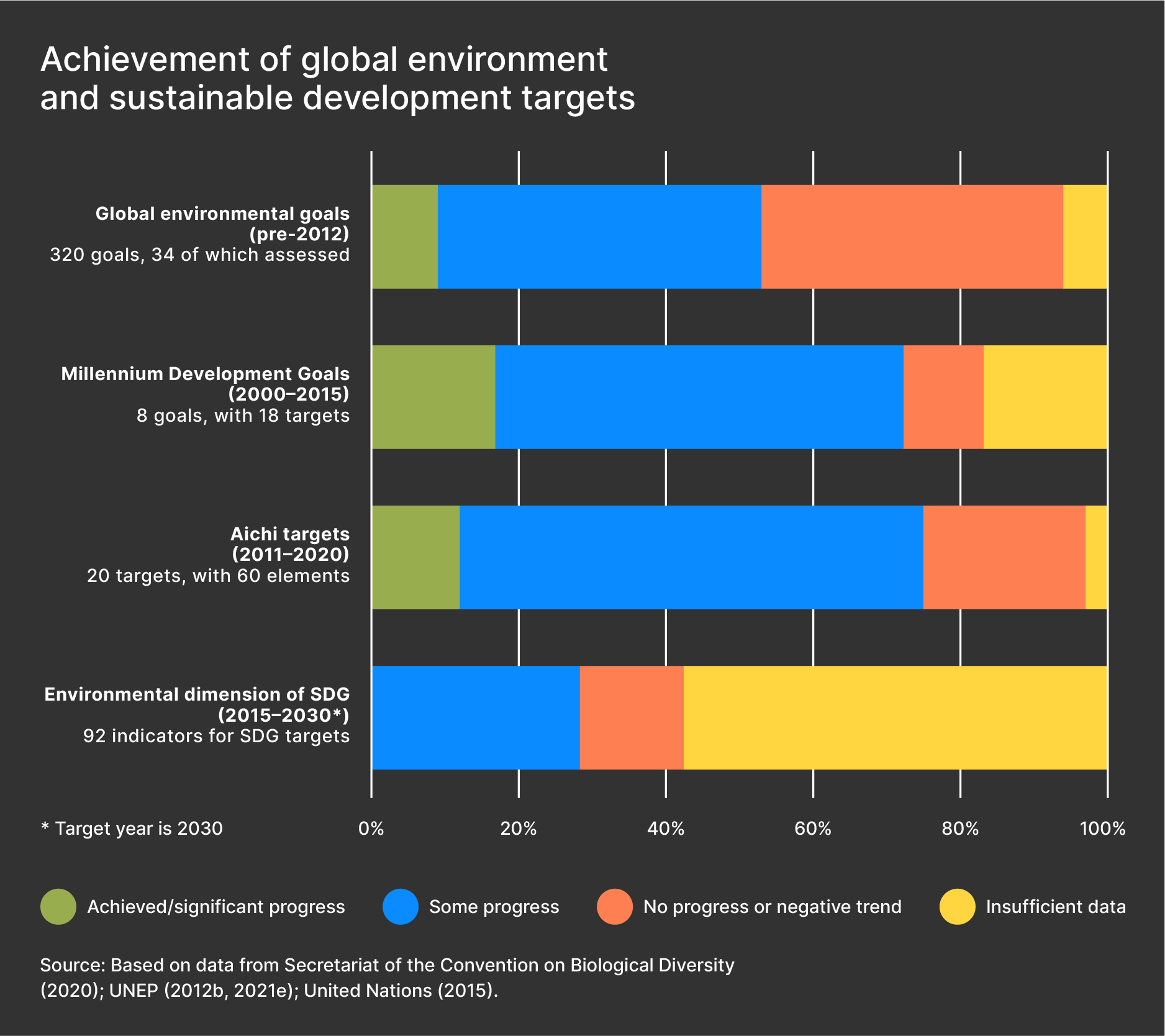

The intertwined crisis of human and planetary development was first recognized at the 1972 Stockholm conference, and the framework for environmental action conceived then has delivered political and scientific activity, but the outcomes remain insufficient. Supporting measures remain too weak to deliver on the goals and lead to actions in accordance with our knowledge. So far, only about one-tenth of global environmental and sustainable development targets have been achieved, and outcomes and impacts for a healthier planet remain insufficient. A new watershed moment is needed at Stockholm+50, where decision-makers and leaders have the opportunity to start closing the significant ‘action gap’.

While no country today delivers what its citizens need and want for a good life without harming our planet’s systems, a ‘low-carbon life’ is possible – and should be a good life that is easily accessible to all. The coming decade is crucial to directing our world towards a sustainable trajectory. Bold and science-based decision-making is needed.

Watershed moments

The world we live in now is very different from 1972, and from the future we want.

Fifty years after Stockholm 1972, humans are causing unprecedented change to the global environment and are risking tipping points with major and irreversible changes in our lifetimes. Climate change has already caused widespread adverse impacts to nature and people, and limiting global warming to 1.5°C is beyond reach without immediate, rapid and large-scale reduction of emissions. Biodiversity and ecosystems are deteriorating worldwide, and goals for conserving and sustainably using nature cannot be met by current trajectories.

Unsustainable production and consumption patterns put a healthy planet and sustainable development at risk. The use of natural resources has more than tripled from 1970, and continues to grow.

The use of these resources and their benefits are unevenly distributed across countries and regions. Inequality is immense, between nations and within nations. The social and economic costs of inaction are predominantly borne by the poorest and most vulnerable in society, including Indigenous and local communities, particularly in developing countries.

The growing inequalities extend to future generations and the quality of their lives, with accelerating environmental change and increased risk of breaching tipping points. High-income countries must drastically reduce their footprints, especially in light of their cumulative footprints over time, to avoid closing development pathways for low-income countries and future generations. This requires transformative action and addressing our economic systems as the core driver of many of these problems.

The intertwined crisis of human and planetary development was first recognized at the 1972 Stockholm conference, and the framework for environmental action conceived then has delivered political and scientific activity, but the outcomes remain insufficient. Supporting measures remain too weak to deliver on the goals and lead to actions in accordance with our knowledge. So far, only about one-tenth of global environmental and sustainable development targets have been achieved, and outcomes and impacts for a healthier planet remain insufficient. A new watershed moment is needed at Stockholm+50, where decision-makers and leaders have the opportunity to start closing the significant ‘action gap’.

While no country today delivers what its citizens need and want for a good life without harming our planet’s systems, a ‘low-carbon life’ is possible – and should be a good life that is easily accessible to all. The coming decade is crucial to directing our world towards a sustainable trajectory. Bold and science-based decision-making is needed.

From urgency to agency

With Stockholm+50 we must move from acknowledging urgency to taking actions that enable a better future for all.

The world has agreed on a vision for sustainable development and a common future – Agenda 2030 – which still needs to come to fruition. In 2022, we have the means to act and we are better equipped for change than ever.

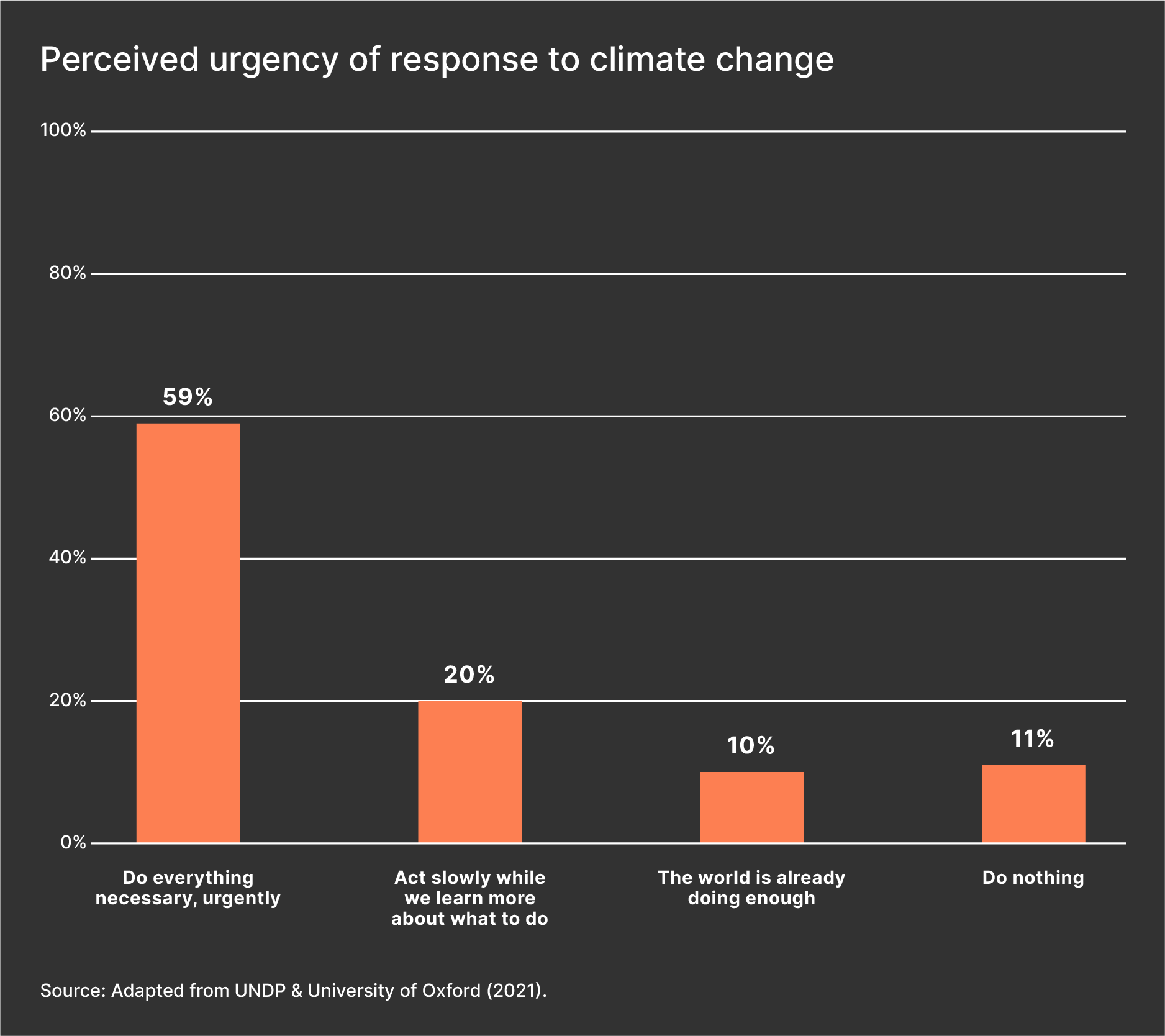

There is growing momentum for change. Public opinion reflects the urgency and indicates people’s willingness to change their lifestyles. Youth worldwide are both exercising and demanding more agency to fight climate change, environmental degradation and inequity. Key technological development and uptake has occurred faster than anticipated, and evidence continues to build of the many wins and co-benefits from taking climate and sustainability action at a policy level.

Now we need to address the speed with which we need to act, with stronger incentives for action than for setting new goals or making more commitments.

Decision makers at every level will need to compress timescales for decision-making in this decade to be transformative, without compromising values of democratic legitimacy and stakeholder consultation. Simultaneously, time horizons must be extended to make bold long-term plans, avoid locking our societies into unsustainable infrastructure, accommodate time lags, and reduce intergenerational discrimination.

We can start to accelerate the pace of change, at both international and national levels, with discussions at Stockholm+50.

We must make 2022 a new watershed moment for a sustainable future on Earth.

Changes initiated now, large and small, can redirect us in the long term.

Redefine the relationship between humans and nature, achieve lasting prosperity for all, and invest in a better future.

Keys to unlock a better future

Based on a synthesis of scientific evidence and ideas, this report calls for action under three broad shifts that would take us to a more sustainable development. The recommended actions proposed, if initiated now, can accelerate change, large and small, for the long term.

Redefine the relationship between humans and nature

The past 50 years – and even the past 5 years – have seen huge losses and degradation of nature globally. Humans have altered 75% of the planet’s land surface, impacted 66% of the ocean area, and destroyed (directly or indirectly) 85% of wetlands.

Many societies value nature as an instrument, something to be used just for resources; that perspective has driven the ecological decline of the past half-century and beyond. An instrumental valuation often underpins policies and economic structures that in turn shape behaviour and social norms at the individual level.

Redefining the relationship between people and nature will require redressing this imbalance. Deep changes across societies, economies and communities must be taken to achieve this shift: how we live in our cities, how we produce food, how and what we learn, and the knowledge and rights that inform our choices.

Actions include:

- Integrate nature in cities and urban areas – Local governments can promote human-nature connectedness through green architecture, infrastructure and access to nature in the towns and cities where most people live and work, as a way of both seeding transformative change through shaping values and providing immediate climate, biodiversity and health benefits.

- Protect animal welfare by including it in sustainable development governance – Animal welfare matters morally, and many of the ways in which we currently interact with animals also limit our ability to achieve sustainable development goals and have negative impact on the environment. Stronger protection of animal welfare will help build human-nature connectedness, and can also directly or indirectly benefit many other societal goals.

- Expand and invest in nature-based education – Education policy and school curricula that connect children with nature can contribute to repairing our relationship in the long-term with nature, while preparing next generations to make sustainable decisions. Inspiration can be taken from Indigenous communities’ nature-based education.

- Recognize Indigenous local knowledge and the Rights of Nature – Greater recognition of Indigenous local knowledge can make nature conservation more effective and support Indigenous rights. Assigning legal rights to nature can be a way of limiting extraction of resources – and can also lead to recognition of nature’s intrinsic values and change societal behaviour over time.

Ensure prosperity that lasts for all

The amount of natural resources extracted globally by humans each year has tripled since 1970. High-income countries have consumed most of these resources, with consumption footprints that are more than 13 times the level of low-income countries.

Ensuring lasting prosperity for all and bringing emission and resource footprints within ecological limits requires a complete rethink of our ways of living, and a shift in social norms and values that drive human behaviour. It requires redefining prosperity at all levels in society and economy.

Actions include:

- Make a sustainable lifestyle the easy choice – Efficiency-oriented options and nudging measures for making lifestyles more sustainable are insufficient; systemic and transformative measures are needed. These should actively create enabling infrastructures, reconfigure systems and amplify social norms around ‘sufficiency’, as well as new global governance initiatives to address equity in these transitions.

- Purchase function, not product – Households, businesses, and government agencies can switch from purchasing products to acquiring functions of products, cutting down the volume of materials we use and waste. Supportive regulatory frameworks and changed social norms on ownership and reuse could have a transformative effect on scaling such business models and reducing ‘material throughput’.

- Make supply chains better for both humans and the environment and ensure that integrated supply chains bridge the technology and economic gap between developed and developing economies. Sustainable patterns of production should include prospects for new jobs and skills, scope for additional investment, higher interdependency in co-creating and sharing prosperity, social safety nets for the vulnerable, and environmental integrity.

- Align national statistics with sustainability goals – Move beyond GDP by adopting indicators that help measure progress towards the vision of sustainable development, such as indicators on inclusive wealth and indicators recognizing the caring economy. Global governance and convergence on alternative metrics are needed to reduce the risk for first‑movers.

- Change the selection environment for innovation – The upstream selection environment for innovation has a cumulative impact on technological development. Common sustainability standards and principles should be applied to guide innovation; international organizations can work to harmonize these and demand adherence for publicly funded innovation.

Invest in a better future

To ensure prosperity for all and redefining our relationship with nature, investing in a better future is necessary. Today, we have the paradoxical situation of a massive amount of capital ready for sustainability investments, yet persistent funding gaps in low-income countries.

The funding gap for the SDGs globally has been estimated at USD 2.5 trillion by the OECD, while UNCTAD estimates that the value of sustainability-themed investment products in global capital markets increased by more than 80% from 2019 to 2020. Action is needed to not just mobilize capital for sustainability, but to ensure sufficient levels at lower costs, supporting allocation to places and sectors in need, and transitioning out of unsustainable practices and capital goods.

Actions include:

- Recognize and enhance public funding of innovation and co-development of technology – Mission-driven public investment can contribute to sustainability-oriented innovation systems. These efforts are promising for both high-income and low-income countries. To bridge the technology gap between rich and poor countries we need a new paradigm of ‘co-development of technology’, particularly in critical areas of clean energy, health, and sustainable agriculture.

- Incentivize active engagement in private finance – Investors should engage more actively to ensure sustainable finance becomes the norm. At a global scale, private investors are increasingly interested in monitoring the environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of their investments, but through shareholder initiatives or direct engagement with the firms in which they invest, they have much more power to transform sectors or industries.

- Raise adequate private finance – We need to address scale, regulation, balance and risk for emerging markets to access investments for sustainable infrastructure. Creating multi-risk, multi-country hedging platforms can lower the cost of capital and bring more private and institutional investment into developing countries and emerging economies.

- Reduce the perceived risk of sustainable investments and raise the perceived risk of unsustainable investments, for example through allocation mandates on lending portfolios. Many low-income countries cannot de-risk financially underserved sectors and technologies. To overcome this barrier, risks can be pooled across countries and then de-risked through a common fund.

Decision makers and policymakers should dismantle barriers of policy incoherence and poor incentives, weak multilateralism, limited accountability, and unsustainable international finance.

These prevent our acceleration towards sustainable and equitable societies.

Improving conditions for change

For the actions called for in this report and beyond to become reality, and for change to be transformative, the conditions for change must improve.

Ample opportunities exist for leaders to tackle structural barriers that hold back effective action, by improving policy coherence and ensuring strong and consistent incentives for action; renewing multilateralism by rebuilding solidarity for the common challenges we face; and by creating a culture of accountable promises.

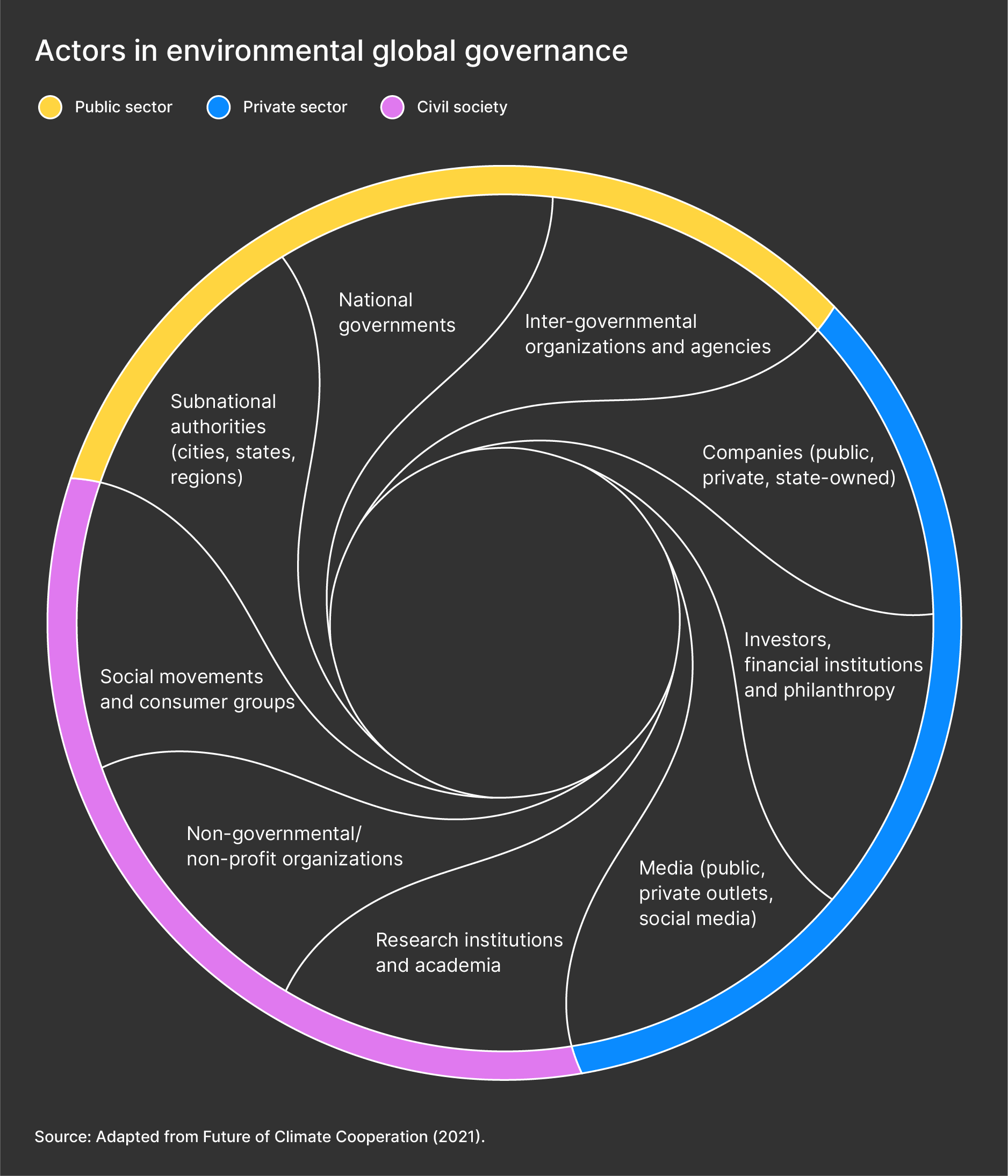

The institutions that were meant to solve the challenges of the past might very well have created some of the challenges of the present. Since 1972, our increasingly globalized world has shifted to governance shaped by a complex set of actors, working within a multitude of institutions at different levels, and with varying sources of agency.

The rules, norms and institutional structures we have now may or may not be ‘fit for purpose’ for the 21st century. They must ensure progress in human development for all, equity in access to resources, sustainability for nature now and for future generations, and justice for the most vulnerable.

The structural barriers of policy incoherence, weak multilateralism, and lack of accountability must be decisively tackled to enable effective action on redefining humans’ relationship with nature, ensuring lasting prosperity for all, and investing in a better future.

Opportunities include:

- With more actors and stakeholders participating in global governance today, many more routes are available to take action. However, conflicts of interest and uneven power relationships must also be recognized.

- Governments and international organizations must make their policy mixes coherent and consistent towards sustainability goals, in order to increase incentives for action, by adopting new practices and tools for more integrated and systemic policymaking.

- The gap in trust and solidarity between countries acts as a barrier to new agreements, to raising ambition and to accelerated national implementation. Opportunities exist to renew multilateralism, to more effectively tackle environment and development crises, and to rebuild solidarity: developing multilateral responses to chronic risks, replacing technology transfer with a new paradigm of ‘co-development of technology’, and setting norms for the global financial system.

- Countries, companies and citizens have to be held accountable for their actions and their inaction. We need new imaginative mechanisms for nurturing constructive accountability, which incentivizes and leads to bold action and change, rather than threatens and leads to pre-emptive action and reduced ambition.

Accelerating change

Half a century after the 1972 Stockholm Conference, which can be considered a global awakening to the entwined nature of human and environment development, this report synthesizes scientific evidence depicting how we have fared since. Given the world we live in today, the report provides guidance for how to unlock change for a better future.

The next decade will drive what happens to us and to the planet in the next 50 years and beyond. We must act now if we are to have any hope of reaching a sustainable existence in some of our lifetimes, in our children’s and our children’s children’s lifetimes.

Setting small and large processes in motion today can allow us to progress on the principles that were established 50 years ago, at the first UN meeting to bring together humans and the environment, towards a better future. We repeat the same call made in the 1972 UN Stockholm Declaration for a new watershed moment in 2022:

A point has been reached in history when we must shape our actions throughout the world with a more prudent care for their environmental consequences. Through ignorance or indifference we can do massive and irreversible harm to the earthly environment on which our life and well-being depend. Conversely, through fuller knowledge and wiser action, we can achieve for ourselves and our posterity a better life in an environment more in keeping with human needs and hopes.

A youth vision

The report Charting a Youth Vision for a Just and Sustainable Future, written by young researchers from SEI and CEEW, presents a four-part future vision built on solidarity, living with nature, and equality, health and well-being for all.

Send your views or enquiries to info@stockholm50.report

About us

SEI is an international non-profit research and policy organization that tackles environment and development challenges. SEI was founded in 1989 and is named after the Stockholm Declaration of 1972. We look to the Declaration as the origin of our mandate, and we fulfil that mandate through research and engagement.

CEEW is one of Asia’s leading not-for-profit policy research institutions. The Council uses data, integrated analysis, and strategic outreach to explain – and change – the use, reuse and misuse of resources. The Council addresses pressing global challenges through an integrated and internationally focused approach. It prides itself on the independence of its high-quality research, develops partnerships with public and private institutions, and engages with the wider public.

Advisory panel members

Ajay Mathur (Director General, ISA), Andrew Norton (Director, IIED), Antonia Gawel (Head Climate Action, WEF), Céline Charveriat (Executive Director, IEEP), Charles Mwangi (Co-Chair, GEO-6 for Youth), Dominic Waughray (Consultant), Elliot Harris (UN Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development, UNDESA), Fatima Denton (Director, UNU-INRA), George Varughese (SEI Associate), Janez Potočnik (Co-Chair, IRP), Joanes Atela (Senior Research Fellow, ACTS), Johan Kuylenstierna (Chair, Swedish Climate Policy Council), Johan Rockström (Director, PIK), Julio Berdegué (Regional Representative, FAO), Margaret Chitiga-Mabugu (Professor, University of Pretoria), Melissa Leach (Director, IDS), Michael Lazarus (Senior Researcher, SEI US), Nicole Leotaud (Executive Director, CANARI), Niki Frantzeskaki (Professor, Swinburne University of Technology), Nitin Desai (Chair, TERI), Oksana Mont (Professor, Lund University), Pushpam Kumar (Chief Environmental Economist, UNEP), Sébastien Treyer (Executive Director, IDDRI), Shardul Agrawala (Head of the Environment and Economic Integration Division, OECD), Ulrika Modéer (Assistant Secretary-General, UNDP), Wang Yi (Vice President, CASISD) and Yasuo Takahashi (Executive Director, IGES).

Image credits

Title: Karn684/Getty Images

Watershed moments: Schroptschop/Getty Images, Yutaka Nagata/UN Photo, Uniquely India/Getty images

From urgency to agency: Basia Asztabska/Getty Images, Thomas Barwick/Getty Images

Keys to unlock a better future: Pidjoe/Getty images, Hugh Sitton/Getty images, Uwe Kazmaier/Getty Images, Manuel Elías/UN Photo, Alex Liew/Getty Images, Afriandi/Getty Images, Sellmore/Getty Images

Improving conditions for change: Travelism/Getty Images, Pavliha/Getty Images, Anneli Sundin/SEI

Accelerating change: Wysiati/Getty Images, ibigfish/Getty Images

Youth vision: hadynyah/Getty Images

Visual branding and graphics bydesignbysoapbox.com